WEEK

3

KINSINDAN

A hands-on approach to healing in a

trice

By TAI KAWABATA

Staff

writer

Lying on your back, you pull up your

shirt and push down your pants a bit. Your partner gently

touches your navel, then moves their fingers slightly down.

|

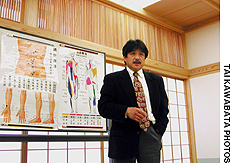

| Satoshi Kono

|

No! No! No! It's not what you think!

Yes, your partner may be a member of the opposite sex --

but their fingers never descend more than three finger-widths

from your navel. And their countenance is nothing if not

serious.

What's happening here is a practical class for students of

a form of medicine called kinsindan (literally, "muscle

diagnosis"), which is claimed to have almost magical healing

powers for certain health problems.

|

| One student practices detecting

another's hardened muscles at a Tokyo kinsindan class

run by Satoshi Kono. |

Just listen to 50-year-old acupuncturist Satoshi Kono, one

of Japan's 20 to 30 practitioners, for instance. Kono, who

teaches kinsindan in Omori, in Tokyo's Ota Ward -- where he

also has his clinic -- recounts the tale of a lady of about 70

who had compression fractures of the vertebrae and hip bones.

"She could hardly walk," Kono explained. "And she could not

even put on socks by herself.

"But then, after doing a kinsindan diagnosis, I pasted a

tiny triangular piece of yellow paper on a treatment point on

her left leg, and another white piece on her right hand."

You guessed: Eureka!

According to Kono, the old lady promptly stood up and

nimbly began walking without any difficulty. And let's not

forget those socks. Thereafter, she could don them all by

herself.

"The treatment -- just consisting of pasting tiny pieces of

colored paper on the body -- made the movement of the lady's

joints and muscles smooth, enabling her to walk," Kono

declared.

Two months off workIn another case, a 38-year-old man

was hardly able to write or type due to pain in his right arm,

and had been off work for two months as a result. However,

after Kono pasted a piece of white paper on his left hand and

a piece of black paper on his right foot, he immediately

became able to write without any pain or difficulty. To

stabilize the effect, Kono applied acupunture to the man's

torso, and the next day, he went back to work and has not

reported any return of the symptons since. The man paid 7,000

yen for the treatment.

But is this exclusively Japanese practice mere

superstitious hokum?

Certainly not, according to Kono, whose father Tadao, 84,

an acupuncturist from Hamada, Shimane Prefecture, developed

kinsindan in the 1970s, and publicized it in a 1986 book

titled "Kinsindan Ho (Kinsindan Diagnosis Method)."

Tadao Kono used to practice the Hashimoto Method of

bloodstream diagnosis to treat his patients, Kono explained.

That method developed by Masae Hashimoto before World War II

involves feeling along arteries to sense not only the pulse

but also the blood flow and many other aspects of a body's

condition.

However, because that diagnostic technique was so highly

skilled, Kono said, that his father sought a more

straightforward method to hand down to younger generations.

This he found after becoming acquainted with Applied

Kinesiology, which was developed in the 1960s by George

Goodheart, a Detroit chiropractor.

Goodheart propounded the theory, and practiced on the basis

that each internal organ is connected with a muscle or group

of muscles, and that problems with an organ manfiest

themselves in a weakening of that muscle or those muscles.

Hence AK treats the afflicted organ by restoring power to the

related muscle or muscles.

Kono explained that his father found he could diagnose

organic problems by detecting a hardening of the related

muscle or muscles. So, in kinsindan, organs are treated by

measures that relax the related muscle or muscles.

And the form this treatment takes is (don't laugh) simply

tying colored string round the wrist or ankle or applying

triangular pieces of colored paper to the appropriate points.

Kono, who studied kinsindan under his father after

graduating from acupuncture school, explains: "The hypothesis

is that the skin can recognize a color and that the skin is an

eye. The color serves not as a stimulus but as information. By

receiving the information, the body's inherent mechanism to

automatically restore itself to optimum balance kicks in.

"But the outstanding thing about kinsindan is that if a

color is applied to a correct treatment point, the effect

appears instantly. Just one or two colors will do. Three

colors at most."

In fact, the six colors used in kinsindan are white,

yellow, red, black, pink and blue -- each corresponding to a

certain "system" in the body.

Treatment of course starts with diagnosis -- which involves

touching various precisely defined points around the navel and

abdomen. If hardness is found, so kinsindan theory dictates,

the system related to that point -- be it the spleen, lungs,

liver, heart, kidneys or whatever -- is ailing.

However, if several hardnesses are found, to determine the

prime problem zone, practitioners unveil their secret weapon:

a pencil-like stick with the North pole of a magnet protruding

from one end. This they apply to all the hardened diagnosis

points until they find the one on which contact with the

magnet relaxes all the related muscles -- so indicating the

prime clinical culprit.

After an appropriately colored paper triangle is applied to

the corresponding treatment point, treatment is then over.

If you, skeptical reader, are tempted to titter, then Kono

says all you have to do is test kinsindan for yourself.

To really bowl yourself over, he says, just try touching

your toes without bending your knees and see how far you get.

Then tie a black string around the right wrist if you are a

woman, or the left if you are a man, and try touching your

toes again. Eureka! Just see what happens.

"My hope is that many people learn the kinsindan technique

and become like barefoot doctors who can help family members

and friends and reduce dependency on hospitals," Kono said.

But if you've got flu, he added, then go and see a

physician.

The Japan Times: May 15, 2005

(C)

All rights reserved |